5. Loneliness, isolation, alienation (disconnection from the norm and from peers)

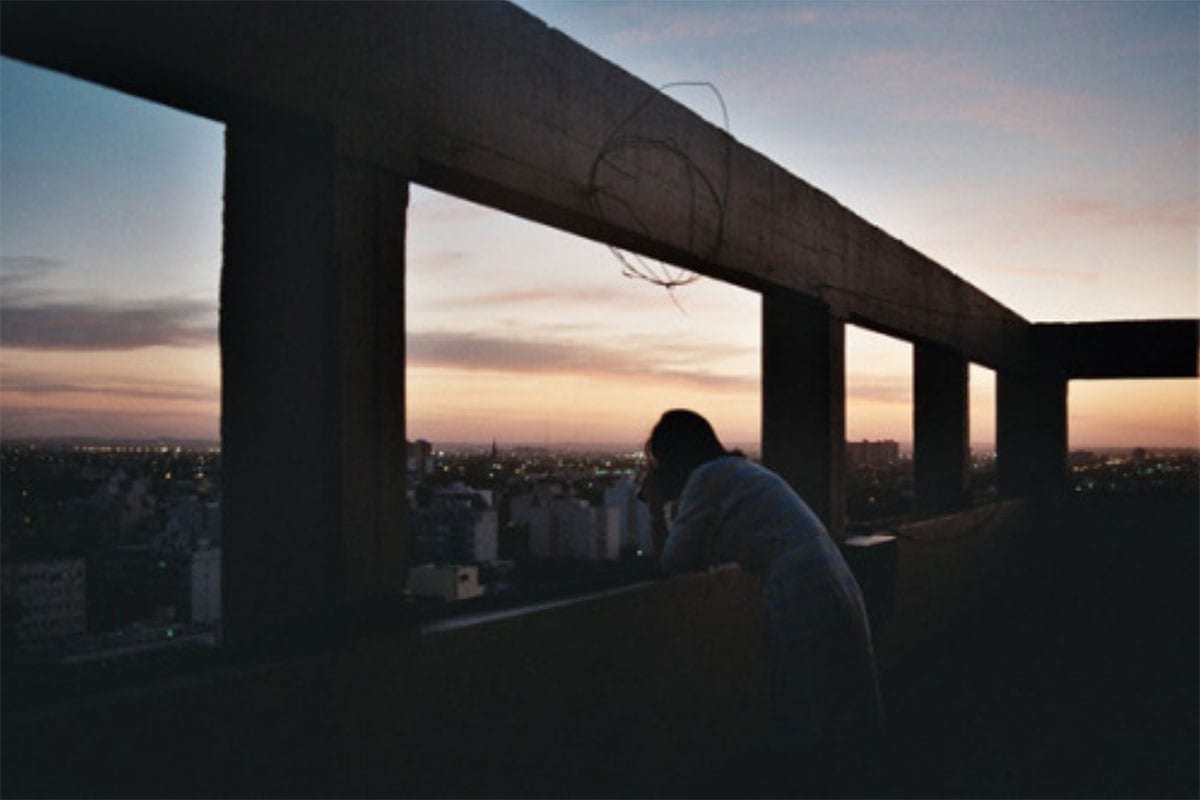

When a partner or close loved one dies by their own hands, we as the closest survivors, have been thrust into a new paradigm, a reality without any signposts. Suddenly a fissure’s appeared in the way we used to see and experience the world and now nothing can be trusted. The structures we normally held onto for conscious or unconscious support have collapsed. Our minds have been fucked by the unnaturalness of the sudden and terrifying suicide of our loved one. But the structures are still in place for everyone else; their minds are still in tact. We are forced into this new reality alone. This reality shift, unfortunately, creates an empathic barrier between the immediate survivors and everyone else. Months after the death, other people’s lives have gotten back to normal, ours haven’t and may never in fact, be normal again. Unless they’ve gone through it, it’s impossible for anyone to know what this death (yours and your beloved) is like. Nothing anyone says or does helps; they’re offering help from another world- a world that no longer has any bearing on where we are. The old world goes on around us like nothing’s happened. But for us, time stands still on the day our beloved left. We are left alone in darkness trying to make some sense of a tragedy we didn’t ask for. Four months after John died, I was rudely awakened by the fact that it was my 3oth birthday. I couldn’t believe it; time had actually passed, life had continued, and somehow I had aged. And aged I had. While my friends were going about the humdrum of their normal twenty something/thirty something lives– work, school, partying, career planning, family building— as was appropriate for their stage in life, I felt like I was a hundred years old wrestling with emotions and facing my own mortality in ways beyond my 30 years of age. While I was figuring out how to breathe without my beloved or how to express my volcanic rage at my fucking life, my peers’ carefree chitchat, ironic joking, and conversations about pop culture, current events, or relationships seemed meaningless, frivolous, and insignificant. It was old world stuff. And I was too old to care. I had had a firsthand trip to hell and back; battling through my grief and scrounging up strength to find a will to live gave me a perspective about myself and about life that most people don’t quite find till later on or perhaps when their own parents pass on and they have to confront death.

As time goes by though, and the months turn into years, the sense of disconnect from others fades as the rawness of the wound has subsided and it’s no longer a bleeding hole front center on my chest. My trip to hell has faded somewhat into the background and I can choose to enjoy material world frivolity, play, and most importantly feel joy and humor in any capacity. In fact, the senses are heightened and the capacity for connection to life and its endless pleasures, and to people living with all ranges of suffering is deepened and expanded.

6. Suicide temptations.

One of the biggest factors that makes experiencing the loss of a loved one to suicide unique is that it inspires suicide ideation in its survivors. It is not widely known by most people, but in fact, according to the suicidology literature, if you have survived a suicide, you are at risk for your own suicide. On the suicide hotline where I worked, we specifically ask our callers if they are survivors to find out how likely they are to make their own attempt. If you are a survivor, there’s a greater chance you might take your own life. The grief is that acute, that intense. Additionally, widows in general, are a group of people notoriously at risk for suicide. A suicide widow, therefore, is even more at risk for her own suicide.

Suicides in general, give others who are suffering permission to take their own. If someone else goes first other people in pain are more apt to follow. Hence the copycat suicide phenomenon. According to the Suicide Prevention Center in Los Angeles, suicides occur more frequently than homicides, however, the media doesn’t report the amount of suicides because of the tendency for people to mimic them. The more suicides are reported in the news, the more people make attempts. And so too with the death of a very close loved one, especially a partner, spouse, husband/wife– the temptation to follow our loved one through the opened door of death is magnified and highly dangerous. In facing the suicide of a loved one we are confronting our own mortality. How badly do we want to live?; how badly do we want to die? Which desire wins out? Which carries more weight? If a beloved or child has died by suicide, half of our being has been murdered. The lingering question is how can we carry on with half a self? How do we repair and rebuild the missing half? It’s an enormous task and requires much strength, tenacity, and will power. And in the early days and weeks after a suicide (especially after funerals and memorials), when life feels so dark and cold, so lonely, we barely have the energy to hold our bodies upright let alone rebuild. We have to somehow try to survive this danger zone until we find sufficient reserves within us to propel us forward and until we find deeper meaning to our loss and greater reasons to live. But until that time comes, the haunting, the desire to reunite with our loved ones, continues.

I hope these last three posts have resonated with all the survivors out there reading this and it helps you make some sense of what you’re experiencing and why it’s so painful. This is not an easy road. Please remember you are not the only one walking this path. Others around the world are going through their own grief and feeling the same kind of bleakness and suffering you feel. You must hold on. The pain does lessen, and in time, as you continue with your healing process (whatever form that may take— dance, prayer, meditation, writing, horseback riding, therapy, grief groups, meditation….) you will emerge a stronger, more whole version of yourself. So stay with it.

Leave A Comment